In the well-known 1955 novel by Vladimir Nabokov, the 12-year-old Dolores Haze is sent to a girls’scout summer camp. Little does she know that her step-father Humbert Humbert (no typo here, his name is really Humbert Humbert), is responsible for her mother’s sudden death, which he had been planning and dreaming of for a while, and is coming to pick her up and take her away from family and friends. After all, the very reason Humbert got with Mrs Haze in the first place was to be close to her daughter, the little Nymphet – as he calls her – Lolita. Lo is a girl of her time, and in many ways she is a good observer of the nonsense of her time too. She says:

The Girl Scout’s motto (…) is also mine. I fill my life with worthwhile deeds such as – well, never mind what. My duty is – to be useful. I am a friend to male animals. I obey orders. I am cheerful. (…) I am thrifty and absolutely filthy in thought, word and deed.

Lolita, 1955, p. 114

I know what you´re thinking: this is not what we’ve been promised. And yet, it is.

Many novels – or other pop-culture media for that matter – are significant to the definition and representation of gender roles in western societies. There are reasons I’ve chosen Lolita: the simplest explanation is that I like the book very much. However, it was the idea that a 12-year-old should be attributed some sort of magical powers, residing in her sexuality, to explain and even justify Humbert’s obsession, that persuaded me. (Note to the humans and non-humans currently scrolling down this post: you won’t find the plot here, so if all this doesn’t sound familiar, and you can’t really understand what I’m talking about, go google the book or watch the film).

In time we’ll come back to the nymphet issue, to that appealing youth, usually accompanied by naivety and lack of self-confidence, which make it possible for people to do to you whatever they want, without you even realising you’re being abused. Here, it’ll be enough to point out that we puellae, like the reader this novel was meant for, are no fool, and we know that Humbert is by no means Lo’s prey. But is, say, Ulysses’ relationship with Circe just as easy to interpret? My point being: why are sexualised female characters so disturbing that have to be portrayed as evil (or stupid enough to die within the first 5 minutes in any horror film – see literature about the final girl for more details)?

Silvia Federici partially answered this question in her book Caliban and the witch (2004). Federici recounts the history of capitalism in a feminist perspective, by linking the witch-hunt phenomenon to the emergence of market economy. As she puts it, capitalism was born and sustained out of human exploitation. Without it, even today no capitalist society would be possible (for example, take away the children mining for cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and we already have a problem). Any society finding itself at the very beginning of capitalism displays the same characteristics Europe did at the end of the Middle Ages: in a word, the necessity to increase labour force and the human exploitation campaigns set up by governments to ensure such increase.

Many many centuries ago, women enjoyed relative freedom and independence. In medieval Europe, they had access to common land, where they could work and survive by feeding off their own produce. They weren’t regarded very differently to men: yes, they weren’t paid as much as male labourers, but they had legal rights and were respected in society, especially in their traditional roles of midwives and healers, and they even led anti-feudal and heretic movements and rebellions.

With the introduction of wage labour (when common land turned into private) and their exclusion from any profession (except for prostitution), women had to depend on their male tutors for survival. Does it mean no more work for women? No, it simply means that they had to work for free, thus diminishing labour costs, and providing more workforce in the form of their children. Such was the sought-after outcome of both church’s and state’s efforts towards a cultural change. (2n note: keep in mind that Federici’s book is an extensive work and I couldn’t possibly cover all the facts she examines, so I’m simplifying here).

It became very important that women had children born within a nuclear family, whose (male) head could claim them as their property. It is no coincidence that Federici borrows Marx’s idea of “primitive accumulation”: the origin of capital which in turns defines class distinction between possessors and non possessors. Ever heard of The taming of the shrew? It is a play by William Shakespear, remade I don’t know how many times, where a husband literally abuses his ill-tempered, nagging and too talkative wife in order to “tame” her, in order to break her spirit, so that she will be useful, a friend of male animals, to make her finally obey his orders. Now that we’ve talked about English literature, the battle of the breeches is worth mentioning too: the idea that wives should want to wear their husbands’ breeches, i.e. have a saying in their business, was ridiculed and became a popular subject for comedies (for example, see John Fletcher’s comedy The tamer tamed or Woman’s prize, 1647). As it often happens today, where sexism is constantly portrayed as funny and therefore acceptable (Silvio Berlusconi and Donald Trump equally took advantage of the way western media covers sexism to create their own “macho” character), back then, theater, literature and the press vilified women’s claim to independence, and in doing so they were encouraged by legal discriminatory regulations.

But I digress. Back to children: ever noticed the obsession witches’ generally have towards children? How the witch in Hansel and Gretel wants Hansel to grow fat so she can eat him? Or how the one from Rapunzel takes the baby girl away from her family and locks her up in a tower? There is some truth to those stories. During witchcraft trials women were accused of infanticide, adultery, contraception, as well as causing impotence and infertility, among other things. If a mother lost a child during pregnancy, or if it died, as it was often the case, what with disease and poverty, it was her fault. In the age of enlightenment and reason, women were described as wild, too emotional, unreliable: male doctors replaced midwives and healers, and took care of anything child-birth related. Sex became acceptable only for the purpose of reproduction, and so older women or single women, who could no longer have children or had no man to claim a son or a daughter, were more likely to be accused of witchcraft, because they couldn’t contribute to the enlargement of the population. As for “single” women, if a woman was unaccompanied, rape and abuse, and consequently banishment or imprisonment, would often follow. Even solidarity or friendship became virtually impossible. Having friends or spending time with other women was discouraged. Did you know that the word “gossip” originally meant “friend – usually a woman” in old English? Don’t worry, I didn’t either. It is telling of how much such friendships were despised.

Western women weren’t, of course, the only victims of capitalism. In any way imaginable, both in Europe and in the colonies, women underwent a process of social degradation, which still left traces today, no matter how civilised and advanced our countries might seem. It lies in our relatives’ comments about our (in)ability to cook, about our negligence or zeal towards housework, our choice (not) to have children. For more details and facts, I suggest you read the book, Federici is a wonderful narrator. The purpose of this post is simply to motivate you to understand. In her memoir Reading Lolita in Teheran, while recounting Zarrin’s defense of The great Gatsby during a university lecture, Azar Nafisi writes:

In her “can’t you see?” there was a genuine note of concern that went beyond her disdain and hatred of Mr Nyazi, a desire that even he should see, definitely see.

Reading Lolita in Teheran, 2003, p. 135

Just like Zarrin, we too would like you to see.

Bibliography & sources

Federici, S. (2020). Calibano e la strega. Le donne, il corpo e l’accumulazione originaria. Milan: Mimesis Edizioni

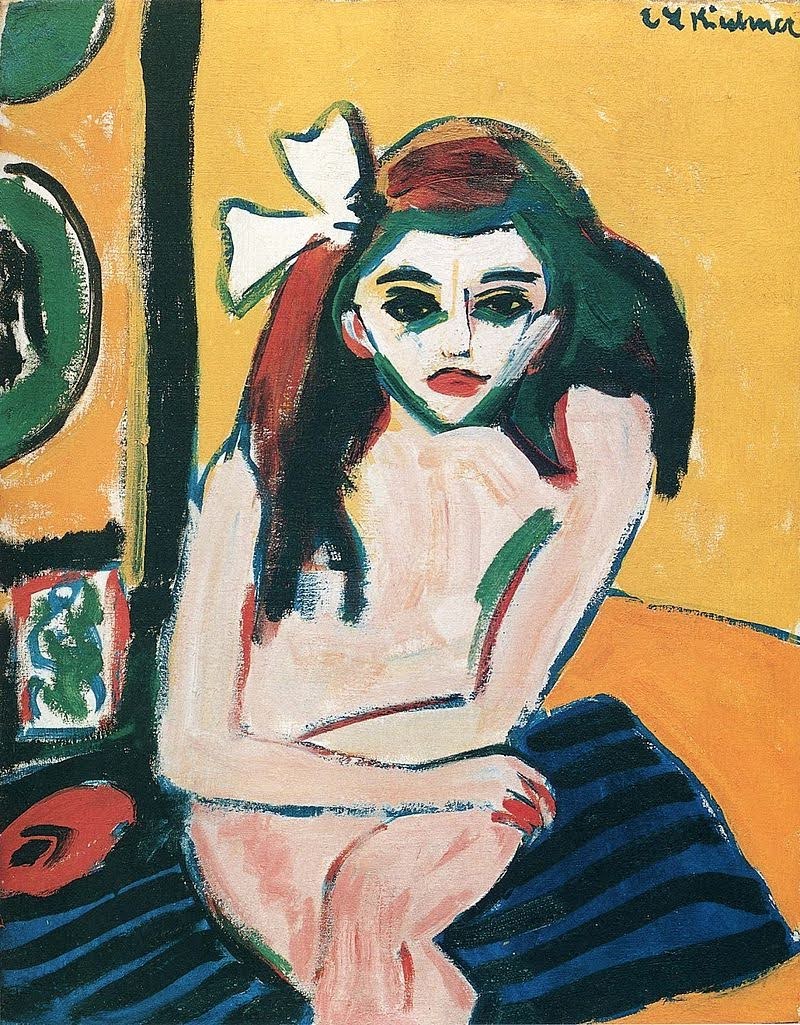

Kirchner, E. L. Marcella (1910). Stockholm Moderna Museet

Nabokov, V. (2006). Lolita. London: Penguin Books

Nafisi, A. (2015). Reading Lolita in Teheran. London: Penguin Books

Leave a comment