Disclaimer:

DO NOT READ THE FOLLOWING ARTICLE*

*unless you are willing to jump in a rabbit hole of deep, dark knowledge, self discovery and uncomfortable truths.

Just joking. By all means, read it. Pain is good for the soul.

So class, today’s panegyric was firstly inspired by the wise words of D. Columbro expressing her concerns on the use of data both in the scientific community and in everyday life. You know, the type of information you leave behind on the World Wide Web while looking for cute puppy videos.

This got me thinking of my experience and especially my university time, not because it was particularly brilliant on my part but because many brilliant minds united their efforts and did their very very best to make me and my fellow uni students understand how most of our favourite subjects were utterly dependent on data collecting.

Now, I am not talking about examining blood cells with a microscope (since I have no science degree) and not even the zealous job carried out by linguists who patiently record all our precious words in big corpora (which I tried doing, with little success). Scientific data as well as linguistic ones are easy for us to digest. As students, we knew we needed them, so it was no surprise teachers asked a question or two about them during exams. The shock came all the same when data collecting was even found in literature, history of art, philosophy. Now, you can accuse me of being naive, but can you honestly admit a girl with no talent can expect to find maths in a lecture on short stories? Did Poe care about numbers? Long story short, Columbro reminded me of this shock and it progressively got me thinking about how bored humans could be to mix oil with holy water like that.

But really, why do we do that? Why do we look for things?

I tried to find answers in art history since a) I think it’s pretty cool and b) I pretend to be an expert on it.

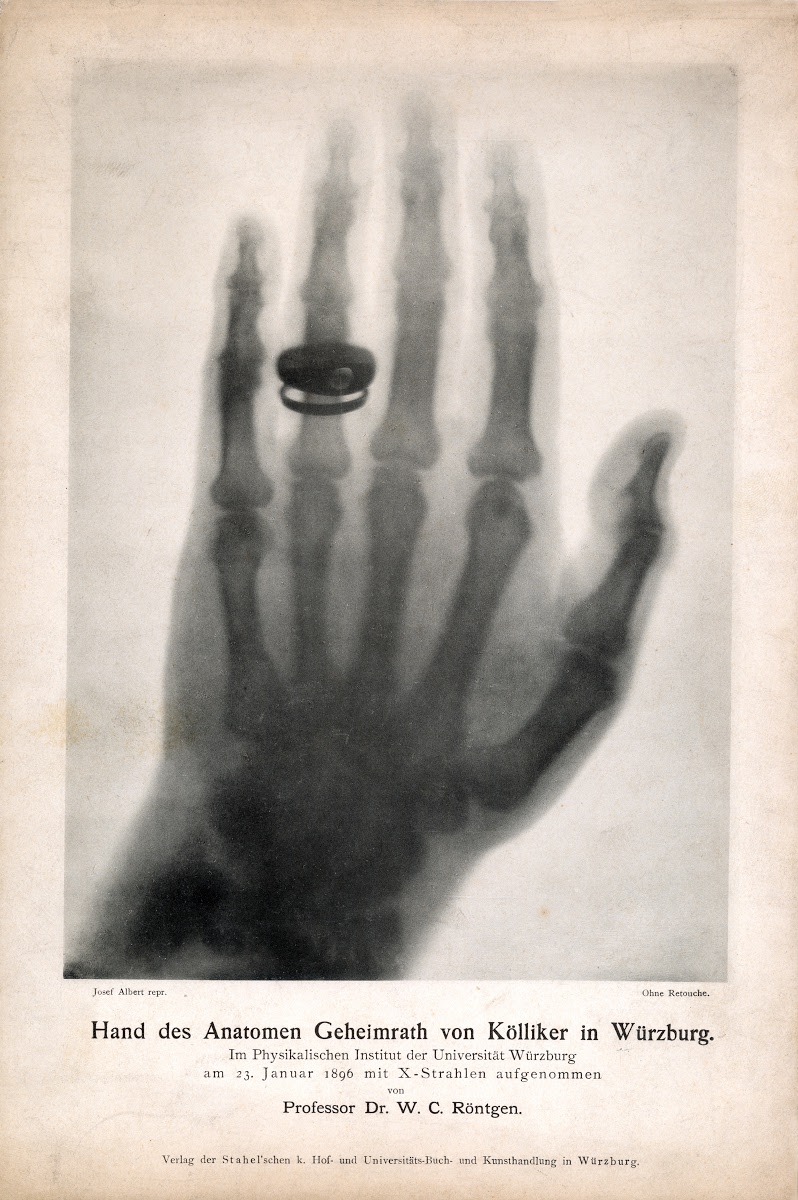

Did you know that x-ray is one of the main instruments of historical research? Since it was invented (don’t remember exactly when, you can Google that) the potential of x-rays has been immediately clear and they soon became a source of income for loads of people creating new occupations. It turned out, not only could you see the skeleton of your hand (and seriously risk cancer) but it was possible to make paint material visible under the many layers of colour on any work of art. Basically, (but do not take my work for it), elements such as lead contained in dying colours react with the rays, so it was possible to see beyond the designs. Before you think “ok, big deal” let’s try and sympathize with art historians for a minute and consider the trouble they go through when dealing with fragile portraits, and then consider being able, all of a sudden, to minimize the effort whilst doubling the results: with x-rays, in fact, it’s possible to date the work of art, distinguish an original from a fake, maybe peek at some famous artist’s mistakes, lots of fun actually. And all that without even touching the work.

Ever fancied what lies behind those precious sunflowers of Van Gogh’s? Some historians certainly have, and are constantly looking for more evidence, marks, secrets to be unveiled underneath those paintings by using all sorts of radioactive techniques.

But what are they looking for, exactly? Can really a painting, which is most likely to be poorly reproduced on a magnet now stuck on your fridge, hide anything mysterious at all? Or still have something to tell, that hasn’t been said already? And even if it did, what do we care? I’m no art critic, why would I be bothered with Van Gogh’s choice of canary over pineapple?

I won’t. Let’s be honest. We liked the picture and would have no reason to explain how accurate the details are or why we chose it over other, equally low quality, magnets. “Isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?” (Douglas, p. 80). We are taught to like the vase of sunflowers and that VG was a great, tormented artist and we are almost obliged to appreciate his works. Hardly ever do we ask why, nor do we raise the doubt about what’s inside that painting that makes it so special and, at the same time, makes all the other still nature paintings nothing but average. We are not looking for fairies either, but we would like to start a conversation about how data is used to understand reality, and how it can fail as well, especially in those cases where the newly found reality utterly collides with the established and generally accepted truth.

I know, it’s a lot to take in. Hear me out.

I first stumbled on the significance of data collection in our society while listening to one of my favourite podcasts, “Dark History”, some time ago, which I had not expected. In fact, that episode was about the origin of the contraception pill, and naturally I was imagining an emotional story of female empowerment, where women take the place they deserve in the predominantly male field of medicine. Or rather, I was hoping to hear such a story. Although, If that was the case, if this had really been a good story about female empowerment, then probably I wouldn’t be here. I don’t know what I would do. Maybe I would be having a blog on how, years and years ago, men used to harass women and how that nasty habit was severely reprimanded and it eventually died out. Who knows.

The fact is, you guessed it, the story was unfortunately about yet another disappointing historical episode where people in power researched and developed new technologies in order to make life difficult for those beneath them. In this specific case, it’s the male very inductive-thought oriented scientists not only trying to control women, but to prevent a specific group of women from having children. The poor ones, the ones with darker skin, the puertorican, the ones always shouting and always making scenes, the ones that apparently cannot keep their legs closed. And since they cannot do it on their own, why not help them? Of course “help” in that peculiar case meant “expose them to unsafe scientific experiments without them fully knowing the risks they were going to encounter”.

I hope I have convinced you to catch up with that podcast, but how has data got anything to do with that?

The puellae’s minds might seem very twisted from time to time. Well, I couldn’t help thinking about those people spending hours and hours registering, comparing, and calculating, in order to carry out their research. Did they know for what purpose the data was being collected? Were they aware of the full extent of their actions, or did they indulge themselves in the idea that rational reasoning is indeed always fair to everyone, even its victims? And had they known it, could they have fully grasped that these numbers were meant for repression? Or maybe there was nothing in those diligently and accurately processed files that could make them realise they were meddling with human lives?

And my very final question is: Can someone with an ever so rational intention end up damaging the very people they should have supported?

I’m afraid I once again have no answer, and the more I look into it, the more examples of hidden bias I find, constantly interfering with our ability to question and criticise whatever idea we’re presented with.

Some may say we’re growing obsessed with “looking for fairies”, but if we have managed to raise the slightest doubt that you too, even when driven by the noblest of intentions might be acting out of bias, then I am very proud of the puellae. And you shouldn’t miss our next post.

Bibliography and sources

Bertelli C. (2017) Storia dell’arte italiana contemporanea, scolastiche Bruno Mondadori

Columbro D. (2020) Le parole che ho imparato. URL: https://app.sparkmailapp.com/web-share/GLALi4aydWZpPjqb6ENfQBAoAGTtYhmivUINUMJ6 (accessed on 9/10/20)

Dalì S., (1949) Madonna di Port Lligat, Marquette University di Milwaukee, Wisconsin (USA)

Douglas A. (2002) The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide, Random House publishing group

Sarian B. (2021) Dark History, episode 5. URL: https://podcasts.apple.com/it/podcast/dark-history/id1568505888?i=1000530255251

Leave a comment